Organizing Principle

by Hanna Andrews

I’m clicking on ‘FRC21,’ and I immediately notice something like an ombre effect, though that’s really stretching it, and this is almost certainly probably exacerbated by my split screen view. I’m noticing the golden-orange-warm and more muted hues of the top handful of works, interested in line, form, which are neatly displayed in a familiar grid floating in white web space. Then there’s more pastels, some effervescent shades, layers of flora, some fauna, and texture, and I’m thinking about the figures, foliage, lines, and layers of oil paint and acid bath and light exposure which refract back to me.

My urge, as evidenced by my own projection of a gradient horizon uniting the twelve works, is to find a through line, an organizing principle. I would like to imagine this has been secured through some kind of subconscious consensus among the dozen participating artists, something in the air. There is a sense of cataloguing present: the name of the show alone, ‘FRC21,’ suggests archive, database. I’m seeing floating pictures, thumbnails, and artists' names hovering below. When I click, there are no descriptions, but instead full work details, and a sleek button which invites me to add the work to my cart.

I’m clicking into each tab, each a little room, meandering through. I’m spending time, magnifying each into smaller rooms like viewfinders, a kind of camera obscura, noticing the textures fed to me via screen, imagining the object in space, the object in front of me, the object being made, the hand, the time.

Arriving at Alise Gaile’s Catharsis, I’m immediately called to zoom. Via magnification, I can open a little window to the tip of the noise, the white of the teeth. This window is not quite a window, but another vista, like a pair of opera glasses, maximizing resolution while maintaining a broad field of view. The snapping rapture of exploding starburst space eye-patched atop a floating face atop a glowing blue flurry. This could be sky, calling to mind Baroque, churning cloudscape frescos or chapel ceilings. It’s undercut by slopes of umber rust, which are canyons and also the suggestion of a neck, a shoulder. There are swathes of light, an outline of the figure like an aura, or a nimbus, surrounding. The mouth is ajar, one single eye gazes through the viewer, through my screen. The title implies release, yet the content points to potential energy: peaks, horizons, the edge of a gasp, light just cresting, thousand year old sediment about to crumble off the face of a cliff.

Ali Brooks’s In and Around Our Little White Houses on Hills Where We Both Work at Hotel Restaurants (and Everything in Between)—immediately: more potential energy (hills) and a long title (descriptive), with a capitalization strategy that mimics modern German or 17th century English, and a parenthetical phrase (a container of ideas within the descriptor itself). Now the image—immediately, color fields, fields of grass. There is a red house, with forest green shutters, perpendicular to the lawns which cradle the house, the first chartreuse shade in an arching L-shape, layered beneath a block of verdant moss. It’s not a white house, and maybe it’s a hotel restaurant masquerading as a house, barn-like, pastoral, yet the title primes the viewer for some extension of artifice. A playful gesture toward something that could be a place and is also a state of mind, a state of life. There might be a storm looming, a gray sky, some backmatter, maybe shrubbery, or a kind of anti-matter, like the furniture of dreams.

Annie Norbeck’s Margin II similarly builds fields of color into a hazy landscape, immediately flooding the viewer with swelling orange, bounded on its perimeters by forest green slopes and lines. Layers of oil, amplified as my mouse drifts over the reproduced image, read as cresting fields of light and space, materialized in swathes of gesture. This is the space beneath the eyes, a sea of orange that could be a sea, the desert alongside a highway opening up into a clearing untouched by cultivation, the soft structure of feet or tire on earth—what is certain is the expanse. The red line cresting over the orange field conjures roads, or further off mountains, which lap either side of a white slope, a slippery shape of snow, salt, sand. Margin II is a screen of warm apricot that invites projection, summoning a feeling which evades the certainty of place with the conviction of feeling and mood, which has no name.

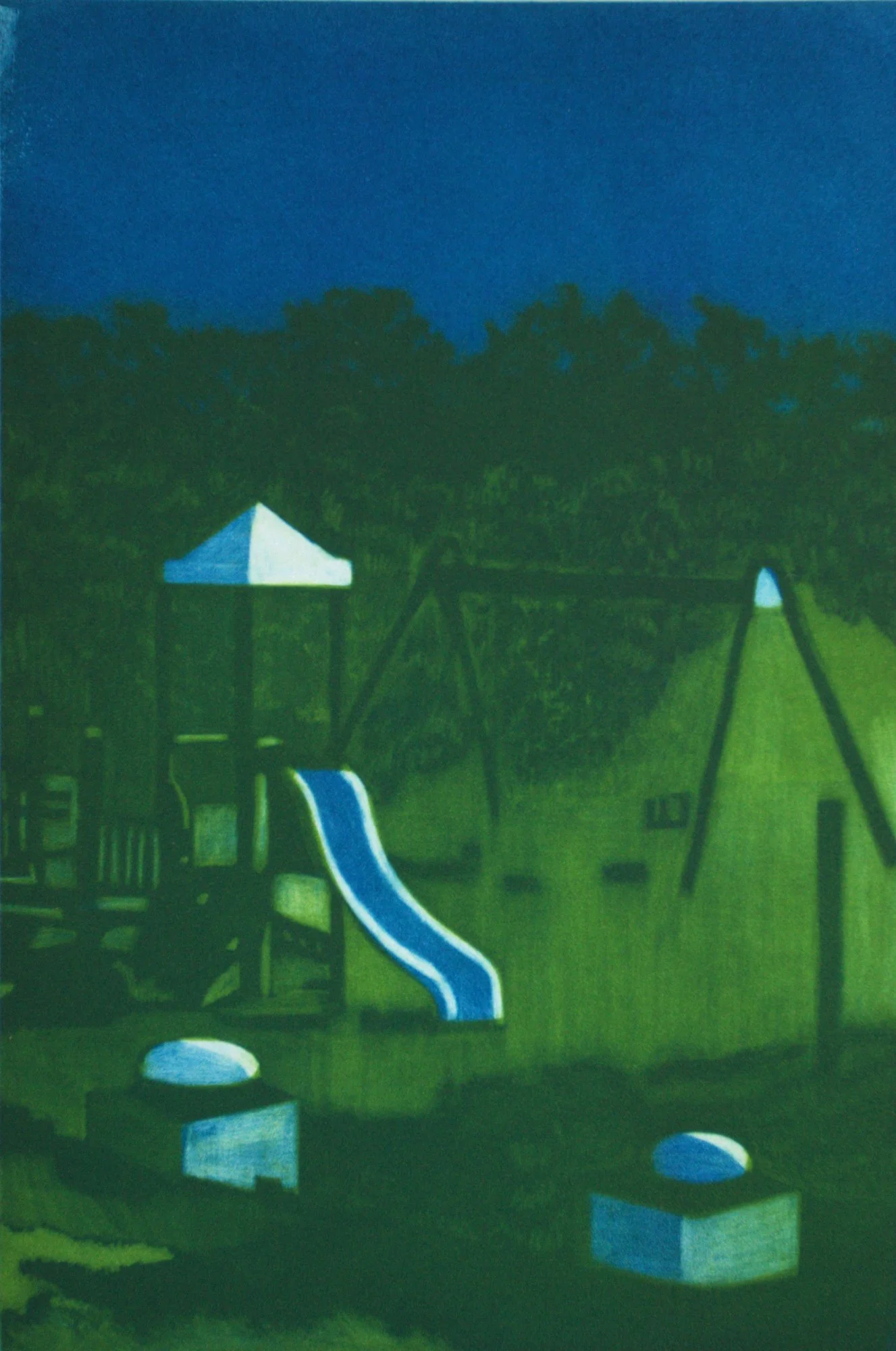

Playground by Arina Heinze is cast in atomic greens and blues, the whites popping with the brightness of night—the certainly of the setting made strange in this electric etching. In this way, the awning covering the slide becomes a lamp, the shining edges of the slide itself snaking like lane lines, guiding the eye through the logic of the picture. Lacey treetops of night sky feather out against nightfall. The lower branches of foliage pick up neon hues in winding mazes, suggesting activity, networks of insects and chirping birds. Two structures, which could be squat pillars marking an entrance, stand watch with considered symmetry, at attention. Heinze’s Playground is haunted by its own ubiquitous architecture of the play space at rest, exposing its creeping contours.

As I move at my steady pace from own work to the next, the ritual of opening tabs, refraining back to the home page (where all works sit in chorus with one another), the feed schema strikes both familiar and novel associations. As Jack Kelley breaks down in his essay for FRC20, “50-50,” the FRC format draws on the intuitive navigation structure of the online grid, which signals both social media and e-commerce browsing functionalities. The virtual exhibition is curated by an artist-juried selection process, which as Kelley elucidates, shifts the “the corruptive, lucrative techniques of digital image economies for their own ends.”

In a sense, I’m thinking about the innovative reversal that’s happening here as compared to earlier artistic experiments with budding technologies, which would later be used for commercial purposes, such as John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem. Launched in 1969 before “900 numbers became big business,”[1] the original public poetry program took advantage of an early telecommunications infrastructure that anticipated pay-per-call consumer services of all stripes. In fact, Giorno credits his project in his posthumous autobiography as the progenitor of “an entire Dial-a-Something industry.”[2]

Over 50 years later, a shift has occurred from brick-and-mortar storefronts to e-commerce platforms, and the frayed ends of Covid online retail boom and bust have been teased out. The super-structure of e-commerce has been inherited, so familiar it’s second nature, and available to be estranged and repurposed.

With these terms setting the tone, I’m left back in the world wide web white space with a group of artworks so varied in content, form, and media that they vibrate with intensity through my screen, and I’m called to continue perusing.

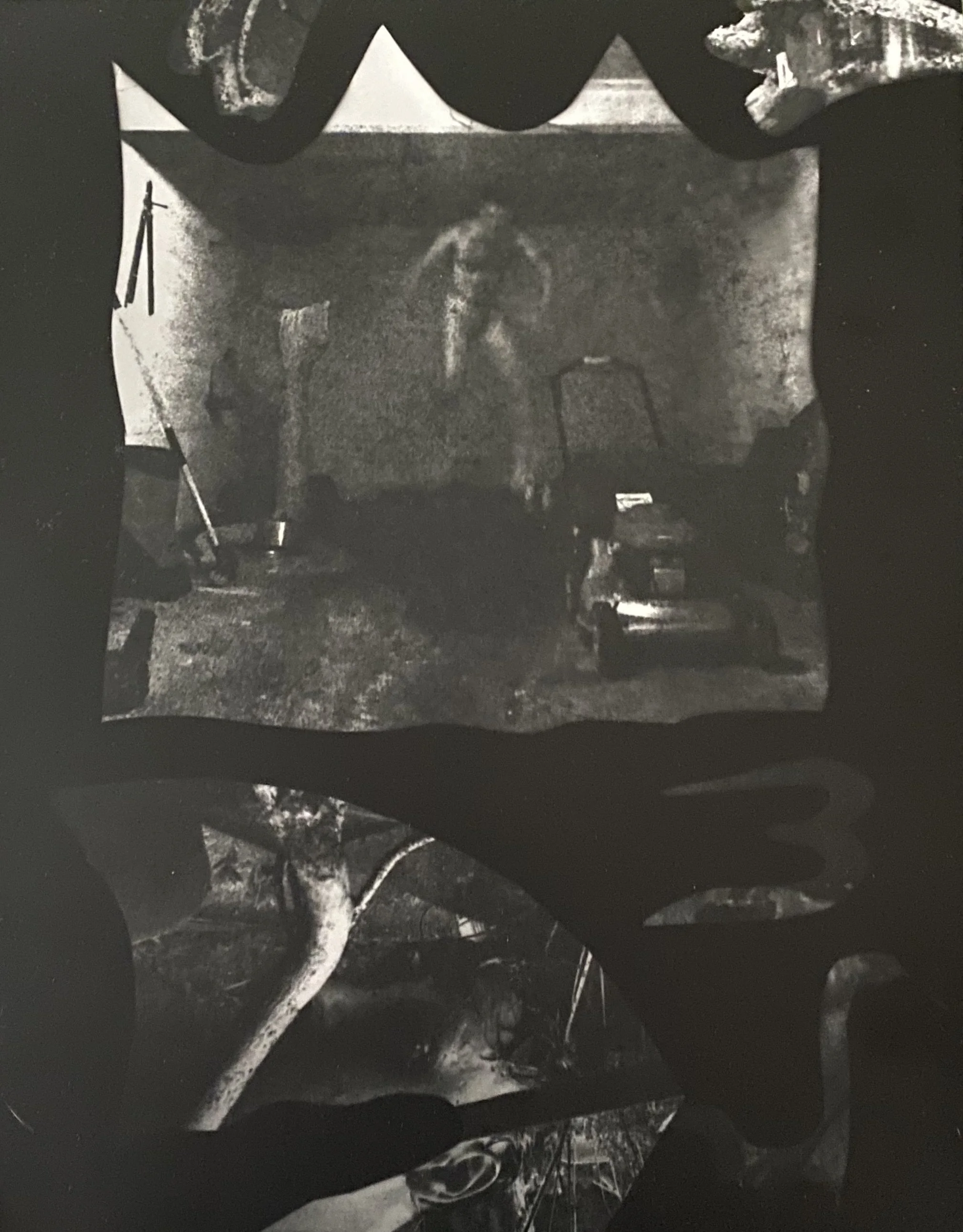

Andrew Allison’s sage, oil, mower (garage), a photogram on RC paper, darkens the collective palate and calls to mind the experiments of László Moholy-Nagy, and other early 20th century adopters of this photographic technique. Here, the abstract potential of the negative image is maximized, therefore estranging the medium from a promise of documentation and the real. While a sense of the scientific looms, as the cut-outs of organic shapes (see a wing, a swan’s neck) might call to mind specimen assembled for observation, the imagery itself feels phantom, dematerialized. A semi-floating figure hangs over the image, a stark juxtaposition against the clarity of the lawnmower’s glistening machine anatomy.

Similarly, Cassie Taylor’s Spending Time with Ghosts overlaps an array of photographic subject matter with mixed media, collapsing swatches of content through various implements of colored pencil, pastels, and prints onto pulp-painted paper. The result is a dynamic scene that stirs some association with discovered underwater treasure, heightened by the Prussian blue of the cyanotype. The detritus of memory feels afoot, as organic forms twist and bloom in crowded company with heavy, anchoring shapes. Frayed edges beg touch.

Meanwhile, Emma Xhaxho’s stately portrait White Dog re-introduces a distinct relationship with surface and tactility, picturing a reclining Borzoi-esque sitter with Farrah Fawcett tresses. This oil painting feels reminiscent of both the dignified aura of 18th century noble hunting dog portraits and the candid sensitivity of David Hockney’s dachshund pet portraits. Perched on a grassy knoll, a pastel pink background casts a rosy tint over the wispy white coat of the Borzoi-esque subject. One dainty paw tucked toward the body, as if posing with hands neatly clasped, the dog seems to emanate an awareness as both sitter and beloved muse. Two white butterflies tug the viewer’s eye, and computer’s mouse, over studied and pearlescent layers of muscle, fur, and form.

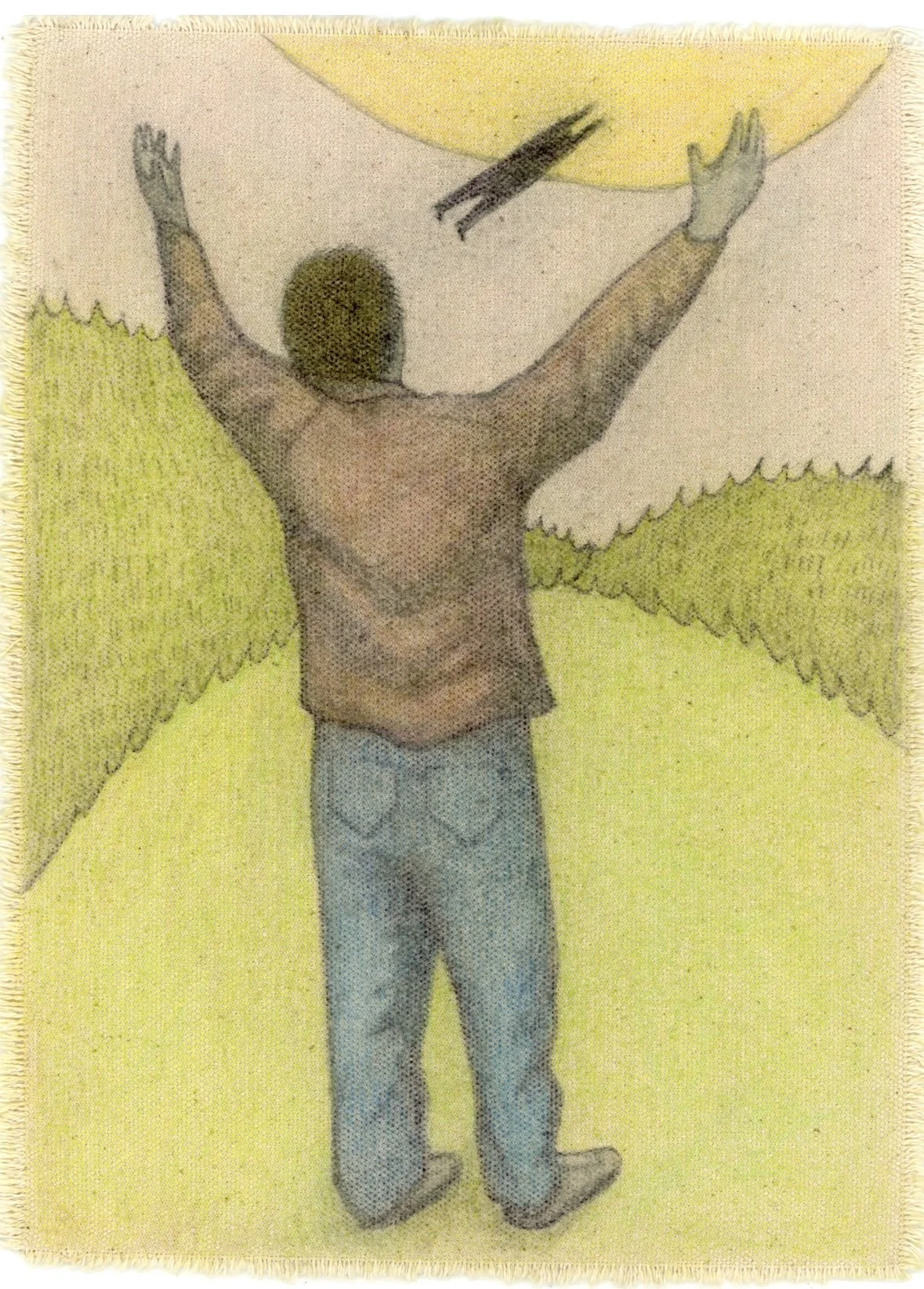

A pastel pink, albeit more muted, sets the scene in Kensey Kendall’s colored pencil on raw canvas, I haven’t learned how. The drawing is full of roundness: the dotted texture of the colored pencil on raw canvas, the open arms of the principal subject, who stands on a grassy hill facing the sun (or moon? a suspended sliver of yolk) in blue jeans. A bat-like, two legged creature flies over the sun/moon, I imagine to the shock or delight of the denim-clad figure. Prickly, hairy hills flank him on either side. The raw canvas brings an emotional clarity to the drawing, picking up a fibrous feel through the unprimed surface. Kendall’s subject matter and sense of flatness calls to mind North American folk art movements, as the figure stands in almost mythic posture against the great expanse of sloping greens and muted yellows.

I’m clicking, revisiting, exiting, thinking about the reproduction of surface, color, scale, the limitations of my zoom window, the ever-increasing volume of my tabs, the e-commerce infrastructure built for quick glances and immediate transactions. FRC’s appropriation of digital marketplace tools alongside an artist-centric paradigm rekindles these platforms around the needs and wants of the makers themselves. In this sense, an ‘organizing principle’ can be imagined not only through the transformation of commercial e-space into an online viewing room which affords slow processing, but also through the spirit of the artists, who look toward structures which broadly seek better conditions for working artists.

Stanza means room in Italian, maybe Giorno’s poetry project on the mind. Except Giorno himself didn’t write in stanzas, he broke the poem into units of found poetry, breaking the language of advertising and consumerism into something white-hot and real.

[1] John Giorno, Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), 236.

[2] John Giorno, Great Demon Kings, 235.

Hanna Andrews is a writer from Southern California. She holds a BA in Creative Writing and Education Studies from Columbia University, where she served as Co-Editor-in-Chief of The Columbia Review. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Photo by Mila Rae Mancuso