Ty Little

Ty Little is a poet living in Richmond, Virginia. Her poetry has been featured in the recently published, We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics by Nightboat Books, as well as Wonder, Sporklet, Metatron Press, and elsewhere.

Divining Movements: A Framework for Participatory Prescience

By Ty Little

The COVID-19 pandemic has deepened our relationship to the shared psychic realm of technology, opening up a space for ideas, desires, and worldly engagement. In projecting our identities and desires into these realms, the desire for a future of increased physical presence has begun to swell, demanding a greater momentum of collective, creative action. Freedom of movement, intimacy, touch, collective gathering and political and social change have become surreal fantasies that are longed for, experienced mostly through the mediation of material. These projections, formed out of our present desires, will lead to the future realities we will embody, through a critical engagement with the past.

Adina Andrus’s stoneware amulets repurpose the remnants of digested consumer goods and carry them on golden, pendulous chains. Constructed out of food wrappers, the delicate detritus hangs on the pieces, continuously haunting them with their histories. These newly memorialized scraps are simultaneously imbued with personal, nostalgic memory for the artist and act as collective signifiers for objects which are instantaneously discarded from memory and experience. Through the inclusion of material that would usually be discarded, we are reminded of their historical fate as inhabitants of landfills. This resurrection and memorialization of nostalgic materials offer a divergence of fate, which does not adhere to the cycle of production, consumption, and waste, as they now remain immortal through reconstitution.

In the tension between their ancient profiles and modern materials, a direct line is drawn between the past, present, and future realities of materials that interact with the body. As amulets, Adina’s works are imbued with apotropaic properties, aiding against the linear cycle of birth and death, which leads to mass waste, the insignificance of memory, and environmental devastation. By using what Andrus calls, “nostalgia-inducing material”, the amulets consciously grope with these concerns, reinviting both the past of the consumer and the material into the future, in which nostalgia has been encased and thus used to critique the historical frameworks of the self-destructive myths of invention, consumption, and discarding. By suspending the material in the present, where the past’s pleasure and memory have become intertwined, Andrus points to personal memory and material memory as a conduit towards collective reimagining.

As the artist and consumer, this material past is memorialized, which itself is intertwined with personal memory and place. As viewers, however, we must engage with another’s past and in doing so, question the previous function of the material. The material’s past-life, in its present embrace of nostalgia, provides the viewer with a snapshot of the architecture of the artist’s home. To memorialize the past through material components is to attempt to return to home. In a moment when home is central to survival, Andrus beckons a return to a personal, past home, through a newly constructed present, providing the possibility to continuously look back for future protection.

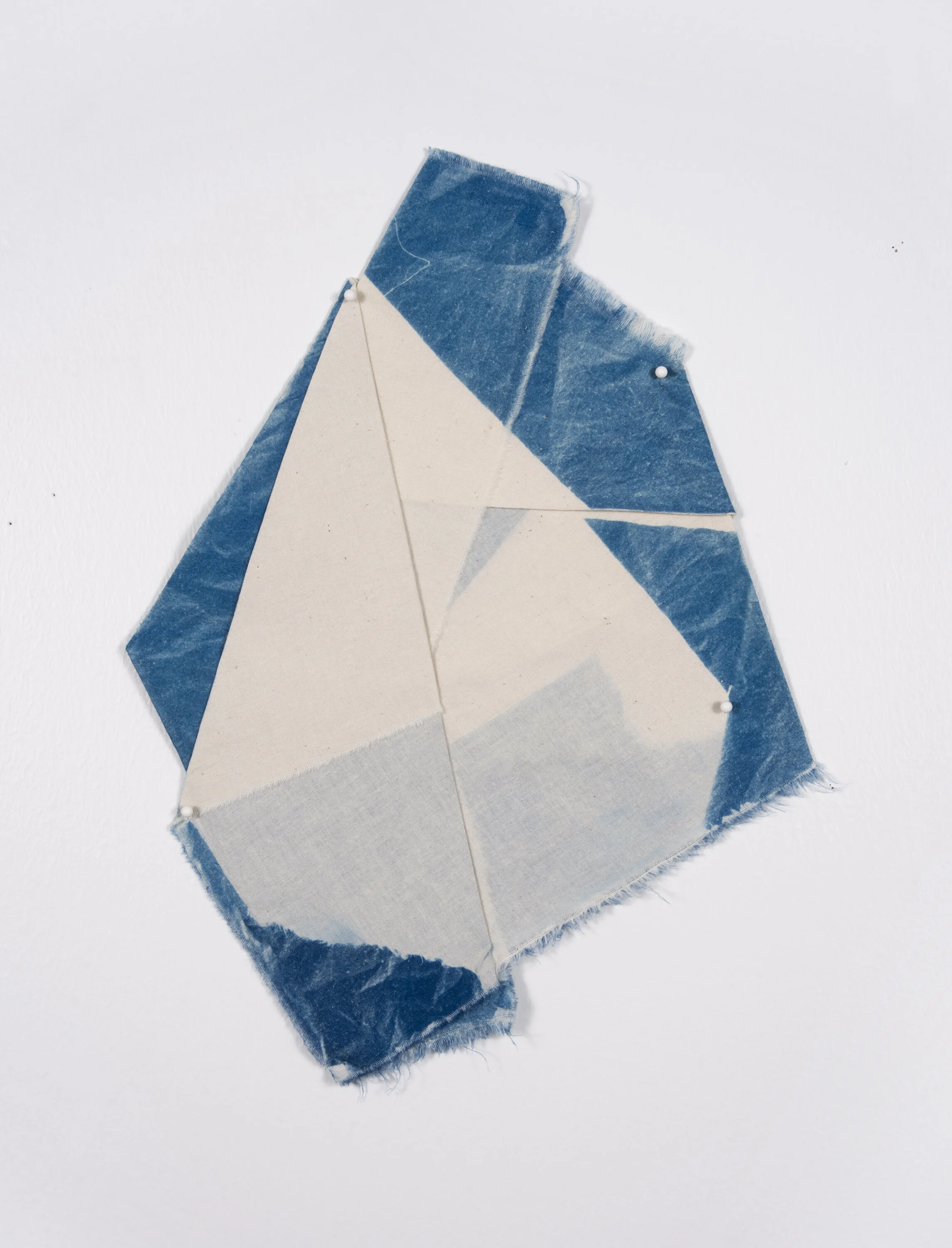

Astri Snodgrass’s work also revitalizes and reimagines the capabilities of material in a historical terrain. These works, however, reimagine through an act of cooperative translation. Through the process of folding, rubbing, printing, and transferring, these works often appear as a series of continuous possibilities by way of translation and adaptation.

Cyanotypes implant muslin, which is folded and redefined. Rubbings are made, then rubbings of rubbings are folded and framed. By enfolding the haunting memories of past material reality, the newly defined architectures of the pieces are engaged in a constant dialogue with the past, disregarding temporal barriers and bodily detachments. Their intermingling of processes creates a present state that is neither new nor old. In retaining the original memory on the material, the work recycles and sustains itself, prioritizing an ideology founded in adaptability and comradery rather than the modern American ideals of novel creation and individualism. The newly synthesized materials are enmeshed, unable to exist without the other.

By redefining the notion of an “original body of work”, these related bodies now cohabitate a shared environment, where history is manipulated and reframed. In an act of continuous rebirthing, which itself is an intrusive flux of bodies from outside of a linear temporal framework, the synthesized materials engage in a reframing of historical possibilities. Through this reframing, a new relationship with the past is performed, ensuring a future of adaptive, collective reimagining.

Lee Piechocki’s paintings portray isolated objects in an illusory, anonymous landscape. His works, “Sweatshirt 01” and “Sweatshirt 02” are catalogs of an artist’s life, self-portraits of daily experience without the presence of the self. By portraying these twin paint-stained sweatshirts, Piechocki points to the present moment of daily repetition. Creating work out of the content of one’s life, Piechocki shows us what content comes out of a time when physical presence must remain stagnant, isolated, and removed from a collective landscape.

The vestments are both journals of survival and portraits of an intimate history with the tools and materials of the artist’s life. There is an emptiness to this history, however, as the body is not present - only the objects. By supplanting the body with empty space, Piechocki places the objects and their original intimate engagement with the body at a distance, gazing at them from afar. Memories of intimate, physical experiences are catalogued, ones that are continuously portrayed, as if to increase the sense of longing for what is missing.

This empty history is also reflected in “Plinth 02: Green”, in which the base of a monument is portrayed, without a body, with a more recent memory of paint. By creating an impossibility of shadow, the base is suspended in a moment of pure possibility - which way will the sun rise? The monument base acts as a reminder of the stable condition of history, while paint portrays modern action and a new understanding of how the present can, and must, engage with history. The shadows, in their impossible stretching, remind us that the future is malleable and able to be redirected.

Sasha Yazov uses painting to mimic the nostalgic visuals of past technologies, creating interconnections between collective histories, personal memories, and material possibilities. The avatars present in Yazov’s paintings are created out of personal desires and a plethora of choices, as in “sims legs”, in which we gain a close-up shot of a newly birthed avatar, possibly before it has embarked on an algorithmic life, or while it stands in isolation in its bedroom. Through this identity construction, they are without particularities and unique features. They are simultaneously lacking identity and perfectly made to fit the desires of the user/painter.

In this, they are projections. Their abilities and lived experiences are infinite, as in “horse riding”, where one rides on a blue-black horse through a city street, barefoot and free. This portrayal of impossibility and surreal fantasy articulates a desire for movement and engagement with a world full of inertia. By exhibiting a physical body disporting itself in a manufactured, material realm, the psychic and technological realms are given precedence for engagement.

Our present moment has shown us that human life can become simultaneously disrupted on a global scale, creating a diversion in the myths we individually and collectively adhere to. These self-fulfilling prophecies, upheld by systems of power, have revealed their narrative weak points, imbuing us with a power to redefine and reimagine our futures. The artists in FRC8 critically engage these historical methods of myth-making, using various methods of repurposing and reimagining to create worlds with more sustainable, adaptive futures, built out of collective desires. By mining memory out of personal histories, these artists look to the past in order to collect materials for this newly defined future. Through acts of translation and material reimagining, they then look toward a future founded in the repurposing of our collective myths, rather than the conservation of them.

March 15, 2021